Maths in the great outdoors

| May 2018Resonating with the work of early years pioneers such as Rousseau and Froebel – as well as Montessori – there has been a recent resurgence of interest in the UK in the potential of the outdoor environment for supporting children's learning.

One of the central tenets of the Montessori philosophy is the connection with the natural world of the outdoors (Montessori, 1946). Children develop a curiosity about and a love for nature through having the daily opportunity to experience the outdoors with structure and purpose. They will use their hands in everyday endeavours focused on the earth and the outdoor environment around them, enabling them to be close to nature.

The outdoor favourable environment is as important as the indoor favourable environment, both working in unison as natural extensions of each other. To support the learning and development of the children effortlessly, we only need to look to see the opportunities the outdoors provides, both with resources supplied by the directress and resources supplied by nature. This environment brings with it nature’s maths: the beauty of shape, symmetry, colour, classification, order, patterning and quantity.

This directly supports Maria Montessori’s description of the mathematical mind: the impulse to produce order out of disorder. Dr Montessori borrowed this phrase from the works of Blaise Pascal, a French philosopher and mathematician, noting that he “…said that man’s mind was mathematical by nature, and that knowledge and progress came from accurate observation.” (Montessori, 1988, p169). Montessori described it as a mind that has the spontaneous ability to organise, classify and quantify patterns and relationships within the context of daily experiences. She recognised that the characteristics of the mathematical mind, order – observation, precision and imagination – can be sharpened with careful nurturing, and nature provides us with the means to do this.

The Mathematical Mind is active in a young child from the very beginning: “in our tiny children the evidence of a mathematical bent shows itself in many striking and spontaneous ways” (Montessori, 1988, p169). The experiences we provide supporting the Mathematical Mind in the first plane of development helps to build the foundations on which all later learning will be built as the child’s development proceeds. We are curious creatures: curiosity drives us to exploration of all types and to understand the world around us in all its aspects. this stimulates essential questions such as why, how, when and what, and this is the curiosity we need to embrace as this is the foundation for creative mathematical learning. Such questioning fuels scientific inquiry, the continuing quest for new, more accurate, or more complete knowledge.

Experiences within wild spaces are also vital to effective environmental education. When we talk about wild spaces, we are not always talking of forests and wood areas – consider letting part of your garden grow wild, replace some of your paved area with raised wildflower beds, give nature the freedom to create the outdoor environment for you. What you end up with may not be tidy but will be a great learning resource. The increasing interest in environmental issues has raised the profile of children's use of the outdoor space in terms of the potential for them to develop positive and caring attitudes to the wider environment (Rivkin, 2000). This rich, sensory, natural environment not only supports children's own investigations (Fjortoft 2004; Waite et al., 2006) but also provides an ideal context for group activities in which the development of knowledge, concepts and skills from across the curriculum are embedded within authentic, purposeful and often real‐life tasks. All of us in our settings will have the basis of Montessori philosophy embedded in our practice, but it is important to also remember that knowledge of children’s development has been increasing over the years. We must use this knowledge to inform our outdoor practice as we support the children on a daily basis in their mathematical development.

Pratt (2011) argues that in order for children to become effective mathematicians they should develop a ‘mathematical disposition’. This, he suggests, can be supported by the doing of maths outdoors, enabling children to develop an awareness that maths is all around them, allowing them to make connections in their learning and experiences of natural materials in situ. Knight (2011) suggests that children will become more creative outdoors where they have freedom to be “innovative, flexible and adaptable” and that this environment will stimulate creative mathematical thinking. When using the outdoors environment the children can construct on a larger scale, explore the world first hand and experience natural phenomena such as weather, the changing seasons and shadows (Maynard and Waters, 2007). Children naturally use mathematical thinking and learn mathematical skills as part of their outdoor experiences. They will count, measure, explore shapes and develop mathematical ideas through their imagination and creative play. They will extend their learning from indoors using nature’s bounty. We should recognise the mathematical potential of the outdoors environment for children to discover things about shape, distance and measures through their physical activity – just look outside for a wealth of ‘mathematical’ resources that children can really get inspired by.

A quick guide to doing maths outdoors

The first tenet in developing children’s competencies is Dewey’s “children learn from doing” theory (Mooney, 2000). In the outdoor learning environment children are active and interactive participants in their learning processes. Dewey thought that rather than saying “the children will enjoy this”, teachers need to ask the following questions when they plan activities for children:

- How does this expand on what these children already know?

- How will this activity help this child grow?

- What skills are being developed?

- How will this activity help these children know more about their world?

- How does this activity prepare these children to live more fully?

Exploring mathematics outdoors is beneficial as it will:

- offer a sense of freedom without the constraints of the indoor environment

- encourage a mathematical disposition and enable children to make useful links in their learning

- Be memorable in that it offers mathematical pursuits in a context not normally associated with mathematical learning

- encourage exploration and risk taking

- Support emotional well-being

- Contribute to children’s self-image of themselves as mathematicians

Conclusion

Maria Montessori recognised the scope for learning provided by nature – by using your vision you can provide the same opportunities nature does in the setting, even in the inner city.

When you look closely, the everyday living world is intriguing and magical, and full of awe and wonder: think of the excitement when a child finds their first ladybird, how many times as a child did you count the dots on the ladybirds back? Young children feel this need for exploration, discovery and creative learning strongly and we will have done our job if we can help them to retain this throughout their lives.

“The future will belong to the nature-smart – those individuals, families, businesses, and political leaders who develop a deeper understanding of the transformative power of the natural world and who balance the virtual with the real. The more high-tech we become, the more nature we need.”

Richard Louv

A few ideas to get you started with a group of children outside

Build a den and then talk together about the shape and size of a shelter that could be built; how wide, tall, or long do we want to make it? How many people do we want to fit inside? Children can make suggestions for the size and use estimation. What size sticks do we need to collect? How many sticks will we need?

Create an obstacle course. Experience climbing up, around, on, under and over, and talk about size, height, and shape of obstacles. How many children can sit on them?

What patterns can be seen in the clouds? Are they changing? How are they changing? How fast or slow are the clouds moving?

Look at the shadows outside, and draw around the shadow made by one of the children. Measure the shadow outline and the child, and discuss the difference; repeat this in the morning, at midday and in the afternoon, and discuss these differences.

Wild area

- Games with grasses: how tall, how many different types, counting

- Games with flowers and sticks: counting, number of petals, different patterns

- Creating shapes and trails by walking through the long grass

Make a collection of natural objects, and then count them

- How many are there? (maybe in a spindle box kind of way)

- Sort them using their size and shape

Digging in the Sand

- How deep is the hole? (Depth)

- Measure using a ruler

- How many more spades to dig to the bottom of the sandpit? (estimating)

- Can you shovel fast with a small spade or a big spade?(time)

Hoist

- How high is the bucket?

- Lower the bucket.

- How much sand have you got in your bucket?

- Is it full or empty?

- Is the bucket heavy or light?

Obstacle Course

- Directional language (over, under or through)

- Positional language (forwards or backwards)

- Time taken to complete (stop-watch, sand timer)

Sand Timer

- Timing

- Turn-taking

- How does the sand get through the small hole?

- Different measures of time 2, 10, and fifteen minutes

- time passing fast and slow

Moving Blocks

- How many blocks fit on a trolley? (counting)

- Is it heavy to push?

Sand Moving

- How many more barrows to empty the sack? (estimating)

- Is the barrow heavy or light to push?

- What makes it easier to move? (problem solving)

Gardening

- Are there enough spades for every one? (counting)

- Planting seeds (counting seeds, planting in a row)

- leaf shapes

- Growing (size, shape)

- How much water do we need? (estimating)

- Have they grown and by how much? (measuring)

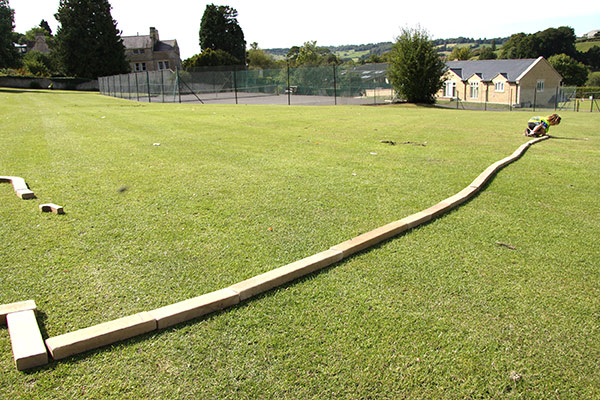

Guttering and marbles

- How far do the marbles roll?

- What happens if we change direction (prediction and experimentation)

- What helps them to roll (problem solving)

- Directional language

Leaf Sweeping

- How many leaves are in your barrow?

- How many leaves on your spade? (counting)

- Are the leaves heavy or light?

Logs

- How many logs can you build up?

- Can you make them balance?

- Do you need to pull slowly so the logs don’t topple off?

- What happens if you build too high? (prediction and experimentation)

Bringing the inside out

- Children need the freedom to work with the material where they like

- Bringing the environments together to support each other

- Bring the physical and the academic together

Resources

Fjortoft, I. (2004) Landscape as playscape: the effects of natural environments on children’s play and motor development, Children, Youth and Environments, 14(2), 21–44.

Malone, K. & Tranter, P. (2003) School grounds as sites for learning: making the most of environmental opportunities, Environmental Education Research, 9(3), 283–303.

Montessori, M. (1988). The Absorbent Mind, Clio Press

Standing, E. M. Maria Montessori: Her Life and Her Work, Penguin, 344

Tucker, K. (2014) Mathematics through play in the Early Years, Sage, London

Waite, S., Davies, B. & Brown, K. (2006) Five stories of outdoor learning from settings for 2–11 year olds in Devon (Plymouth, University of Plymouth).

This article was first published in Montessori International autumn 2015.