Supporting and promoting effective communication within the early years

| October 2023What is early communication, and why is it important?

Communication has become one of the most widely discussed issues within Early Years policy and practice. In 2020, the Department for Education, in partnership with Public Health England, published new guidance to give children the best possible start in this vital area (DfE and PHE, 2020). This guidance came in response to the recognition that growing numbers of young children are being identified as having long-term speech, language, and communication needs, with disparities in the support that they receive. Communication underpins all areas of learning and development, so young children must be supported from the earliest point possible to learn how to communicate effectively. Communication is the most significant indicator of future health, well-being, and educational outcomes (McQueen and Williams, 2022). For many children, language develops quite naturally; as the saying goes, “You spend the first two years teaching them how to talk, and the next sixteen telling them to be quiet”, yet how do we ensure continuous progress for those children who struggle to communicate?

Early communication development

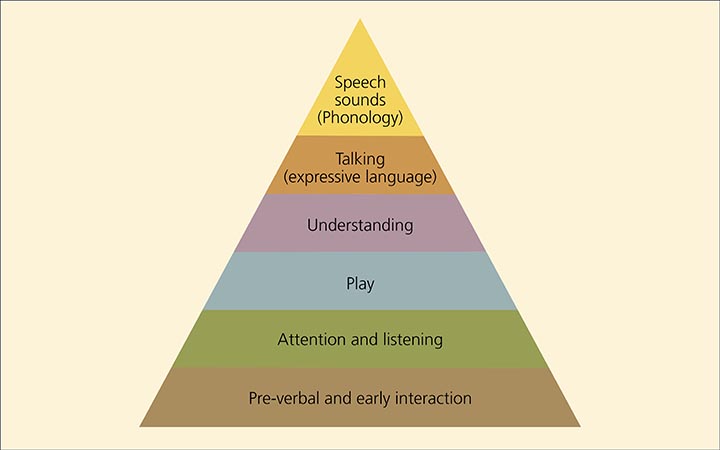

During my years of practice, I have supported many non-verbal children, but this did not mean they were non-communicative. One child I particularly remember was a 3-year-old autistic girl we shall call Hope. Working closely with a specialist speech and language therapist, I implemented the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) with her. Hope had a bank of cards with photographs she would give to me or her friends to communicate her needs, wants and interests. If she needed the toilet, Hope would find her picture of a bathroom and give it to me. Or if she wanted a drink, she would bring me the card with a photograph of a cup. We started slowly with only two cards, but she had a book containing over twenty cards by the time she moved up to school. PECS enabled Hope to communicate successfully. To support a child like Hope effectively, you must first assess their level of development. Knowing their level of communication enables you to plan the child’s next steps and implement targeted activities to support them in reaching the next stage in their development. Is your child listening to other children during play, or are they involved in parallel play only? Are they understanding verbal queues or simply gestures? Are they making sounds or using touch and movements to make themselves understood? The Language Development Pyramid can be a way to begin this assessment.

Children must learn key skills in each pyramid layer, working from the base and moving up to become effective communicators. This model, widely used by speech and language therapists across NHS trusts, is easy to understand, making it accessible to parents and early years practitioners.

Different strategies for teaching communication to children with SEND

While some children may stay within the lower levels of the communication pyramid and need additional targeted support to work upwards, others may have a keen grasp of certain levels but still need to catch up on key foundational parts. The educator adapts their teaching strategy to meet each child's individual needs. A key aspect of teaching communication to children is exposure. Children like Hope need to be in a language-rich environment where they can see and hear communication throughout the day. If they remove themselves from the action, ensure they benefit through some other interaction with a trusted adult or key worker. Other effective strategies can be implemented to further enhance children’s communication skills at earlier levels in the pyramid. Some examples of these include:

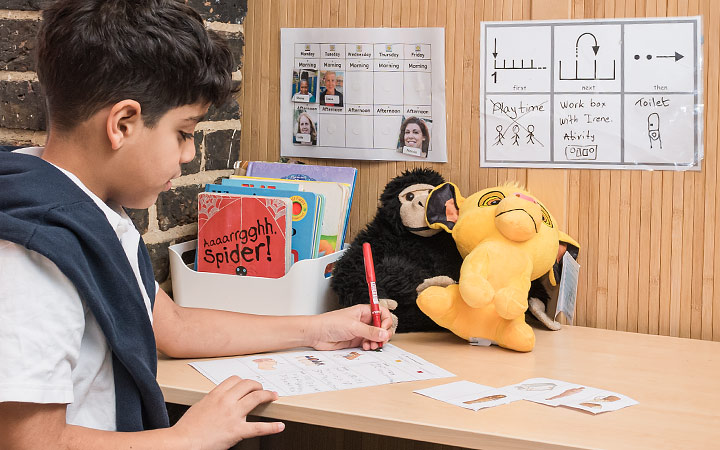

Visual aids

Visual aids are my favourite strategy and can be used at any level within the Language Development Pyramid. They support children in understanding and remembering specific information or instructions. They can be diverse and flexible to meet the individual communication needs of children and can include photographs, objects, symbols or charts. Within a classroom environment, you could have a visual timetable with symbols to represent each activity or event of the day. Whether you are using a simple “Now and Next” board or have a more complex schedule displayed, make sure it supports the child in understanding their daily routine and is not overwhelming. It should be a positive facilitator of discussion between the child and the adult, not just a command centre. Additionally, Photographs or images representing the child can empower them to make their feelings, wishes and interests known. It is important that when a child points to an image, you say the name of the object or activity, so the child begins connecting with the image and the word.

Makaton

Makaton is a multimodal approach which uses symbols, signs, and speech to enable people to communicate. It is a flexible programme that can be adapted to a person’s individual needs and presented at a level allowing comprehensible input. For example, a child or adult may not be able to make the sign for a word physically, but they may be able to point to a sign or symbol instead. Makaton connects to the language development pyramid at all levels as it can support children’s development of pre-verbal and interaction skills and promote understanding and potential progression to speech. As a practitioner, I embedded Makaton into my daily practice across my classroom with all children. Although Makaton targets children and adults with communication difficulties, it can be a valuable resource for language acquisition at any age or stage of communication development. I would use Makaton during key transition times and during daily routines, such as telling the children that it was time to go outside. When attempting to address a class of thirty children and give them an instruction, your voice can be lost in the crowd. However, by saying the instruction and signing the keyword simultaneously, some children will hear what you have said, and others will see it. For Makaton to be effective, a child needs to have a communication partner who understands and uses it with them. By using Makaton across your classroom, all the children can learn it and use it meaningfully to interact with the children who rely on it as their primary communication tool. Applying a whole class approach to implementing strategies, such as using Makaton, promotes peer learning, subsequently fostering communication skills. This will also help create an inclusive environment, enabling children to communicate with their peers multimodally.

Augmentative or Alternative Communication (AAC) systems

AAC systems are tools and methods that enable someone to communicate other than using their voice. AAC systems can vary from low-tech tools and methods (such as using an alphabet, word, or image grid, where a child or adult can point to individual symbols), to more hi-tech, digital devices, which will respond by speaking words aloud. Advanced touch-free digital devices can even track eye movements, converting them into information and responding. Giving a non-verbal person a voice can help educators assess what stage of development they are working at on the language development pyramid. They can listen to a question and demonstrate their understanding by responding to it. Once a practitioner has made a baseline assessment of a child’s level of communication, they can plan the next steps to support them in their development.

Time

Utilising time as a strategy for developing children’s communication may appear to be a simple concept, but often one which is forgotten within practice. As with any new skill, children need time to learn, understand and use language, with opportunities to practice. Young children, particularly those with SEND, require processing time to make sense of any communicative interaction and formulate a response. Each child’s processing time can significantly vary, and you must not rush a child or speak for them. In a busy classroom environment, where you are potentially asking thirty-plus children to make a choice, it can be easy to cut into a child’s processing time and make the choice for them. This can have a detrimental impact on their communication development as they may stop trying to speak as they become aware that they are ‘taking too long’, and it is easier for them to let someone else speak for them. Although giving children time to speak is essential, giving them time and space to be silent is just as important. As adults, we all take moments to reflect on conversations we’ve had. During these times, we often remain quietly in thought, but we do not always afford children the same opportunities. When a child is silent, they are still communicating. Observe their body language, expression and even their reason for not responding. Are they processing the information? Did they understand you? Are they making an active choice not to respond? Everything a child does is telling you something; their silence is as much communication as their behaviour. Perhaps they just need time to tell you and for you to take the time to decode it. Implementation within practice is challenging. Classrooms can be bustling, noisy environments, often with one teacher and an assistant stretched across them, busily implementing curriculum plans and meeting targets. It’s often the loudest children who are heard the most. How can you make time for the quieter children, those who do not have much language or those who play by themselves and need more support to develop their communication? As an educator, this was a challenge I encountered daily, and I needed to find time to work with these children, preferably on a 1:1 basis or, at best, in small groups. Although I planned in specific times to support individual children as much as possible, the most effective strategy I implemented was utilising daily routines and activities. For example, if children were lining up to go into the lunchroom, I would position myself next to one of the children who was quieter and initiate a game of ‘eye spy’, or I would sit down at snack time at one of the tables and talk to a small group of children about their snack, naming each item of food that they had. Although this was only a two-minute exercise, the daily repetition built up core knowledge and measurable improvement.

Key person approach

Although educators can implement strategies and adapt the environment for children to optimise communication development, there is another key ingredient. The positive relationship between a child and their trusted adult will incentivise every communication strategy and allow the child to build on their strengths and milestones. One of the many roles of a key person is to form an attachment with each child and get to know them. Part of getting to know a child includes discovering and respecting how each child chooses to communicate. Overtime, key people can become adept at interpreting the slightest nuances in children’s communication and interactions. However, identifying and interpreting a child’s communication is just one part of the process. The next and potentially most important step is responding to it. Listening and hearing are two separate concepts. Communication is a two-way process; without a communication partner, a child’s attempt to communicate is lost. Listening to a child means acknowledging their communication, while hearing them means engaging with it. If a child chooses not to go outside and play with their peers, you listen to them by acknowledging what they have expressed. However, if you simply dismiss them and tell them they must go outside because it is part of the daily schedule, you have only listened to them. To hear the child, you would engage in a dialogue, find a compromise, or provide them with an alternative activity.

Conclusion

Communication is the foundation of all learning and development and a critical life skill. Lack of language development impacts a child’s communication ability and can be extremely frustrating, leading to poor educational and health outcomes. Some children require substantial and potentially life-long support to communicate effectively. As early years practitioners, we must support, nurture, and promote children’s communication from the earliest point possible. Our role and statutory responsibility is to ensure every child, just like Hope, has a voice to express their needs, wants and feelings. It is also our role to acknowledge that a child’s voice is not limited to the concept of a verbal voice but encompasses all forms of expression, recognising the multimodality of communication.

References

DfE and PHE, 2020. Best start in SLC: guidance to support local commissioners and service leads. Online. Available from: Best start in speech, language and communication (SLC) - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

McQueen, D., and Williams, J. (2022) Supporting the Development of Speech, Language and Communication in the Early Years. Jessica Kinglsey Publications: London.